Yeah, so, I think I’m going to use this blog again. A lot has changed since I last posted. I’ve started and now almost finished college. I’m 24 now. There’s been a massive international pandemic. And, to be honest, over the past five years, the birding blog as a medium has kind of died. Social media has exploded and now it seems like people mostly just post on Facebook and Instagram instead of writing longer form posts. A lot of classic bird blogs are still operational and producing great content, but they just don’t have the impact or clout that they used to. It was for this reason that I didn’t really intend to continue this blog. However, especially as my undergrad is now over, I’ve found myself wanted to write about my birding again– honestly more to preserve the memories for myself than for anything else. So here we are, my first post in five years. It’ll probably look different than it did before. I’m a fully grown adult now with a different (and hopefully more coherent perspective), I’m a lot better at birding now than I was five years ago, and I hope my writing style and voice has improved (although that might be asking for a lot). So if you’re a returning reader from five years ago, or somehow are stumbling on this blog now, I hope you find it entertaining and informative.

Ptarmigan are the kind of birds that seem mythical to many birders. Cryptic creatures of the high Arctic, they seem very far from the everyday lives of most people. It’s for this reason that I became entranced with the idea that in just over a day, I could drive into the range of Willow Ptarmigan. To do so, I would have to head due north from Pittsburgh 17 hours to Chibougamau, Quebec. This past March, with a week off from college for spring break, I decided to do just that.

My friend Jack and I left Pittsburgh at about 5am and angled the car north. We’d barely left Allegheny County limits before it had started to rain– pour down in fact. Looking at the forecast, we realized that the whole Northeast of the continent was covered in precipitation and would remain that way for the rest of the day. To compensate, we cut out our planned birding stops in upstate New York and headed right for the Canadian border in Buffalo. By Toronto, the rain had turned to a sleety, icy, wintry mix which we attempted to battle through to wrangle up some waterfowl before we reached areas without unfrozen water. When the weather became simply too unbearable, we continued our pilgrimage to the north.

By the time we reached Lake Simcoe, the wintry mix had concluded its metamorphosis to snow and the whole world was coated in a fresh coat of white. While this made being outside the car infinitely more bearable than pounding rain, it produced its own set of problems as the roads became increasingly treacherous.

We stopped at a Tim Hortons in Huntsville, Ontario– previously the farthest north I had been in Canada– and assessed the situation. After some deliberation, we chose to soldier on through the lessening visibility and slickening roads. Not more than a few more hours down the road we realized our mistake. Traffic had slowed to a crawl, semis were blasting past us at hazardous speeds, and the road was completely coated with snow. Admitting defeat, we stopped at a hotel in North Bay, Ontario and were asleep by 8pm.

Up by 3am, we discovered that– true to form– the Canadians were exceptional at getting the roads plowed and with the snow having stopped a couple hours previously, the roads were as good as new. We raced ahead until we crossed the border with Quebec right after dawn. Pulling over to survey our new Francophone surroundings, we almost immediately bumped into our first Pine Grosbeaks and Common Redpolls of the trip! Given that Pittsburgh was abuzz with excitement about returning Red-winged Blackbirds and American Woodcocks, driving north had given us the incredible sensation of going back in time and turning back the clock of migration.

As we worked up past the town of Val d’Or, the area became increasingly remote and the roadside birding improved in tandem. We passed by many groups of Pine Grosbeaks perched up in trees along the road, had a pair of Ruffed Grouse on the verge, and even a tree full of Sharp-tailed Grouse nibbling at catkins!

Finally, with a couple hours left before sunset, we rolled into Chibougamau, exhausted after two long days of driving. After checking into our hotel we set out to spend the rest of the evening looking for Ptarmigan. Willow Ptarmigan disperse in the winter away from their tundra breeding grounds. Despite their looks, they’re actually quite capable flyers and are able to migrate a good ways south. They’re also irruptive and will range to various latitudes and in various numbers depending on the year. Chibougamau is about as far south as they can be reliably found and in some years they’re present in impressive numbers– well into the hundreds. The strategy to find them is simply to drive down the main road and various side roads and look for them foraging along the roadsides. They are easiest to find at dawn, but can be present at any time of day. That first evening we checked some side roads which birders had recently reported the Ptarmigan from, but came up empty. What we found instead was a nearly nonstop series of logging trucks rocketing by. We found it hard to believe these wouldn’t flush any roadside grouse and they came by at such frequency that they would never allow any grouse to resettle. Wondering if perhaps a logging operation had started in the few weeks since the most recent Ptarmigan reports, we waiting until nightfall and attempted a night drive for Canadian Lynx. We came up empty– no doubt not helped by constantly having to dodge the logging trucks.

The next morning we tried to same roads again and once again were foiled by trucks which seemed to never cease operation, no matter the hour. Increasingly nervous, we picked a new side road, one we hoped would have fewer trucks and were vindicated when we were able to find a road with no tire tracks at all– a very promising sign. Soon enough we came around a bend and there they were: our first Ptarmigans! A pair running along the roadside. Delightful white balls of fluff, they flushed on our approach and were gone with snappy wingbeats off into the woods. No matter, farther down the road we found a flock of nine, and then a flock of four, and then another flock of three! All in all 20 Willow Ptarmigans, all giving incredible looks as they skittered around, ate berries, and scrabbled in the snow for road grit. The trip’s goal secured and what a sweet victory it was. Watching these beautiful birds, in a stunning landscape, with dead silence except for our breath, the Ptarmigans’ footfalls, and the soft sound of falling snow. It was every bit as magical as I had imagined and was made all the more so by the memory of being in a Pittsburgh Spring just 48 hours before. Needless to say, Chibougamau was still locked in the clutches of winter.

A little farther down the road, we ran into a tidy Redpoll flock consisting of four Commons and two Hoary Redpolls. Bird species are few and far between in the winter this far north, but when you encounter them, they tend to be of high quality as a flock of 1/3 Hoarys evidences!

The next morning, we finally turned south again and headed towards Tadoussac on the St. Lawrence River. Obviously most famous as a fall migration hotspot, this town is excellent in the winter for Harp Seals, our main target there. We also wanted to look for Beluga, a population of which is resident in the river (although easier to find in the summer). On the way southeast, we stopped in a city park in Saguenay to look for Bohemian Waxwings. No Waxwings were to be found, but we did find an excellent “Greater” Common Redpoll. This subspecies group breeds in Greenland and Iceland and is scarce in Northeast North America during irruption years. They’re identified by a combination of their large size, heavier streaking, browner colour, and more extensive throat patch. A series of excellent discussions of this taxon can be found on Sibley’s blog. The taxonomic status of Redpolls on the whole is obviously in seriously flux, but stuff like this reminds us that these will still be fascinating birds to look at, puzzle over, and ID regardless of how they ultimately get broken down along species lines.

We arrived in Tadoussac 10 minutes after the reception of our hotel had closed for the day. When we rang the number given for after hours assistance, the man who picked up informed us that he was “on snowmobile trip in Gaspe” and the number that he gave us did not answer. Perhaps very little is more French Canadian than the one person you need spontaneously being on a snowmobile trip. We found a small motel attached to a restaurant down the road and, tired from another day of driving, fell asleep,

The birding in Tadoussac was excellent. We started by seawatching at Pointe de la Croix where we hoped to spot seals or the distinctive shape of a Beluga back breaking the waves. No whales were to be seen and the only seals were Harbours, but the birding was excellent with large numbers of Barrow’s Goldeneye, a crisp Harlequin Duck, and loads of white-winged gulls. The amazing thing about being this far north is that the white-winged gulls tend to outnumber the others and we saw 75 Iceland Gulls compared to a mere 25 Herrings!

The rest of the day was spent cruising up and down the river looking for marine mammals which we struck out on. We eventually came to the conclusion that we had mistimed our visit. Our hope was to be able to get both target mammals at once, but with the pack ice breaking up by this stage in the winter, Harp Seals seem to have largely dispersed while Belugas have yet to become as common as they will be in summer. Close to sunset, we did finally find one large ice field, and while it yielded no resting seals, it was gorgeous to look at.

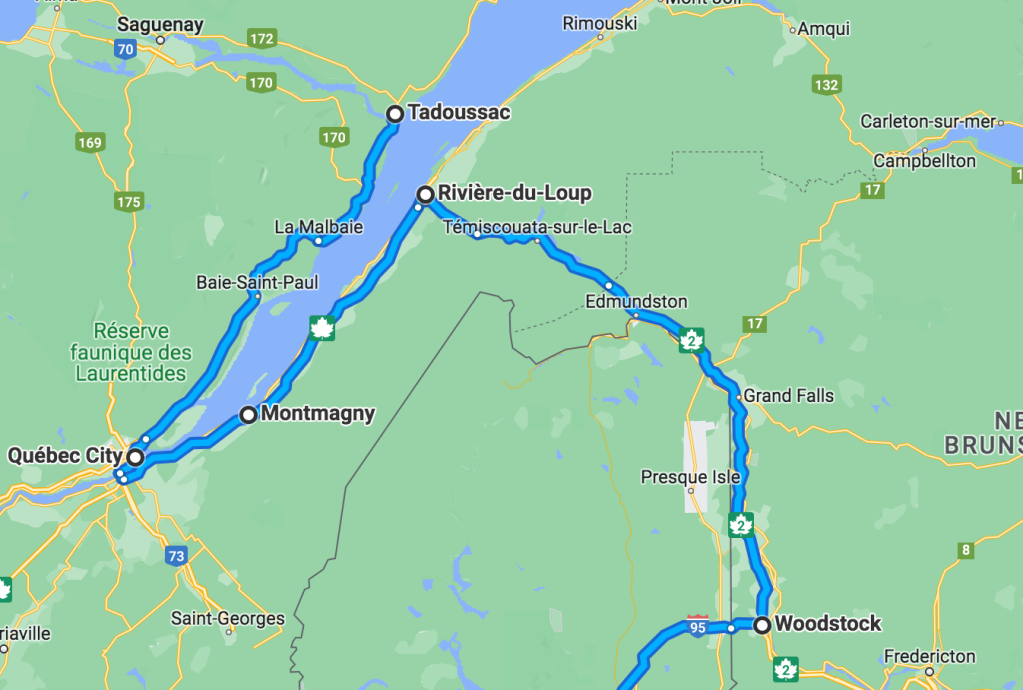

More logistical difficulties faced us the next day. We had originally intended to take the ferry across the St. Lawrence from Tadoussac to Trois-Pistoles. However, every time we’d driven past the ferry terminal, it had been suspiciously empty. We eventually did some googling only to find that the ferry (perhaps unsurprisingly) doesn’t run during winter months. This meant we had to drive southwest along the St. Lawrence all the way down to Quebec City before following the river back northeast (this time along the southern shore) if we were to arrive in our destination for that evening in coastal Maine. This added 6 hours onto our drive due to poor planning.

We made the most of it and got on the road early and ended up with a lovely day of county listing from the New Brunswick highways. By midafternoon, the French had disappeared, the snow was declining, and we crossed the border at Calais, Maine to questions from the border agent if we were coming to look for the (recently departed) Stellar’s Sea-Eagle. Our adventures in Canada had come to an end.

Our last major stop on the trip was to be in Cape Cod, Massachusetts for a spot of seawatching. We had chosen to come back through Maine ostensibly so that we could chase the eagle in the case that it was refound. However, the real reason was mostly that I love the state dearly and have ever since my grandparents lived there while I was growing up, and I wanted to take any opportunity I had to visit and get a few state birds. As we cruised down the Maine coast, we stopped to tick off various state targets including a parking lot Fish Crow, a Snow Goose in the same flock of geese as a long staying Barnacle Goose (which I had already seen the previous November), and some Brant along the southern coast. By the time we reached Southern Maine, the weather was getting decidedly squirrely and snow started to fall heavily as we arrived in Massachusetts. With heavy overtones of the first day of the trip, we checked into our motel in Hyannis and then went out to the Mashpee Pine Barrens to search for New England Cottontail: a scarce and declining New England endemic mammal.

As the snow accumulated and a brisk wind whipped the cape, we couldn’t find any rabbits active. However, despite the conditions, we did find a recently returned American Woodcock peenting and displaying in the road. This birds are always magical to see– especially after having just emerged from the frozen north where no sign of spring had been in sight.

The next day was a wash from seawatching due to the weather so we decided to stay an extra day. This turned out to be an excellent plan as the following day gave un a good seabird flight. Hundreds of Razorbills zipped past the point and mixed in were three of our targets: Thick-billed Murre. Unfortunately, we could only stay out for a few hours before needing to drive back to Pittsburgh and had to start walking back by 11, pleased with the Murres, but disappointed in the lack of Cetaceans. We needn’t have worried as while we were halfway back down the beach a North Atlantic Right Whale erupted off the horizon, breaching out of the water. We stood slack-jawed as it breached twice more before disappearing for good. Distant views: but utterly diagnostic. An unforgettable experience that we were buzzing from the whole drive home to Pittsburgh.

That concluded our trip up to Quebec. We returned to Pittsburgh exhausted from a lot of driving, but pleased with the trip on the whole. I highly recommend going up to see the Ptarmigans. It’s a bit of a long drive, but ultimately pretty accessible to most birders in the Northeastern US. In years with more owls around it could be a really excellent trip. I’ll just have to go back up some day to get the Lynx, Beluga, and Harp Seals…